Myth 1: You need to have a talent for languages

When I was at school, I believed I didn’t have an ear for foreign languages and that I was simply lacking aptitude for it. I remember my friend Frauke, who just seemed to soak in every new word she heard or read. It was impressive. And depressing for me as whenever I tried to learn the necessary vocabulary out of the smelly textbook with faded pages we used, I immediately fell asleep. Seriously. I simply could not focus on learning it. We tried vocabulary boxes, notebooks, calendars, all with little success.

Now, my friend Frauke is certainly a very smart person. She’s holding a Ph.D. in physics now. But apart from her undoubtedly high IQ and her tremendous ability to focus, she had one great advantage: she was raised bilingual. Her mother came from South Korea and spoke Korean at home. In the early 90s, speaking another language at home other than German was a rare phenomenon in central Germany, a region with very little immigration at that time. Her brain was wired for the acquisition of a 3rd or even 4th language.

As research confirms, language knowledge is additive meaning that with every bit of language we learn, we train our brains for additional language acquisition, we actually acquired the „talent“ for language learning. Following the concepts and findings of cognitive research about translanguaging, which focuses on the interconnectivity of the entire language repertoire a person is using, it even makes more sense to see all the languages one speaks and/or understands as one whole language repertoire rather than separated entities.

Myth 2: It’s a long and rocky way to learn a language

But what could have helped me, the 13-year-old girl with almost zero contact with foreign languages, having an easier time acquiring English at school? According to Stephen Krashen, the key would have been extensive exposure to comprehensible input. Stories, songs, films, games, magazines, speeches, talks, and so on using a language I could mostly understand and dealing with topics that would extremely appeal to me. Things I would love to know and spend my time within my native language, my L1.

At that time which feels like the stone ages now, it was fairly difficult to get material like this. I remember there was an American teen magazine at the local library and I was trying to read it with an outdated dictionary that widely ignored youth language. I would have loved to have understood the songs I was listening to, but my level of vocabulary was so low I even couldn’t identify where one word ended and another began. Lyrics were hardly published and I remember one of the highlights of the BRAVO, the no 1 youth magazine in Germany, was the page where they published the lyrics of two top 10 chart hits along with a German translation. I was sometimes in shock to read what our favourite songs were really about. But it was comprehensible input par excellence.

And research confirmed that using CI is far more effective than the textbook methods we still use, e.g. learning the vocabulary and structure first, then practicing it over and over again until it becomes automatized. The challenge for teachers and learners is to find material that has exactly the level we need and is compelling enough to be of learner’s interest. While listening or reading to these stories, learners automatically, effortlessly memorize new vocabulary and structures along the way. I truly believe that this approach is key to igniting the fire for the love of language learning in children.

And our mission as language teachers must be to provide our learners with this kind of material and create a pleasant atmosphere in which „playing“ with languages is welcomed. We must be on the constant lookout for compelling stories in different language levels and, if necessary, being able to adjust them. In our globalized and digitalized world, this has become easier than ever before.

Myth 3 – It’s too late. I should have started as a child

When talking about language learning myth, one giant elephant in the room must certainly not be forgotten: age. A common belief is that you have to start at a very early age to be able to master a foreign language and there has been quite some research about the question of whether or not there is something like a critical period. While there is evidence that it is indeed hardly possible to reach a native-like pronunciation when starting with another language as an adult, but when we look at other features of language the notion „the younger, the better“ seems to be plain wrong.

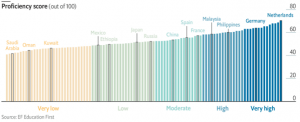

Carmen Muñoz proved in her BAF study that younger language beginners were actually outperformed by older ones. The older beginners, due to their greater intellectual maturity, were not only faster learners overall, but also more efficient. As Steve Kaufmann, a prominent polyglot with knowledge of 20 languages, points out in a conversation with said Stephen Krashen: „Learning a language is all about noticing“, meaning the self-directed recognition of linguistic phenomena in the target language, which a child might find very difficult to do.

What seriously hinders older learners are negative beliefs about their abilities and the fear of making mistakes. To answer these concerns, teachers could, for example, focus on receptive skills such as reading and listening until the classroom atmosphere allows for shyer participants to be more experimental.

And benefits of being bilingual, trilingual, or even multilingual are mind-blowing. Not only does every bit of another language broaden horizons and bring us closer to a true understanding and appreciation of the uniqueness and diversity of human existence, but it can also make your life longer. Maria Polonsky describes findings that show, that the onset of dementia is delayed by an average of 10 years within multilingual brains and the likelihood to get Alzheimer’s disease is in fact 5 times higher in monolinguals compared to those who were brought up bilingual.

How amazing is that?!

References:

Muñoz, Carmen (2016, 3. Februar). Professor Carmen Muñoz at the launch of the Centre for Research in Language Throughout the Lifespan. YouTube. Abgerufen am 10. November 2021, von https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bOP-kmHXapA

Kaufmann, Steve (2013, February 12). Stephen Krashen, an Interview. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pqVhgSvwWYk&t=4s

Polonsky, M. (2015, June 22). Cognitive Advantages of Bilingualism – Maria Polinsky [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-ml2dD4SIk&feature=youtu.be

University of Haifa. (2011, February 1). Bilinguals find it easier to learn a third language. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 6, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/02/110201110915.htm

University of Tokyo. (2021, April 1). Multilingual people have an advantage over those fluent in only two languages. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 6, 2022 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/04/210401112530.htm